January 14, 1920: Oregon Ratifies the Nineteenth Amendment

On January 14, 1920, Oregon became the twenty-fifth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which stated: “The right of citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State, on account of sex.” Most Oregon women had achieved voting rights in 1912 and many had been voting since that time. The Oregon Legislature held a special legislative session from Monday, January 12 to Friday, January 16, 1920, and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was on the agenda. In his “Message to the Special Session” on January 12, Governor Ben W. Olcott expressed his hope that the legislators would give “unanimous approval” for ratification.

Almost immediately after Governor Olcott’s address, Sylvia Thompson (Democrat, The Dalles), Oregon’s only woman in the state legislature in 1920, proposed a ratification resolution in the House of Representatives. At about the same time, Senator Robert Farrell (Republican, Multnomah County) proposed a similar resolution in the Oregon Senate. What appeared at first to be a simple process of ratification quickly turned into a three-day event. Many newspaper reporters followed each dramatic turn as the process unfolded with conflict, negotiation, confusion, and finally, a resolution. An over-eager newspaper photographer added even more interest to the story, leading to charges of “fabrication of news.” By Wednesday, January 14, 1920, Oregon’s House Joint Resolution No. 1, which ratified the Nineteenth Amendment to the Federal Constitution, had been signed and filed with the Secretary of State.

Some sources use Monday, January 12, 1920 as Oregon’s Nineteenth Amendment ratification date because both the Oregon House and Senate passed ratification resolutions on that day. But because the President of the Senate and Speaker of the House signed House Joint Resolution No. 1 on Wednesday, January 14, 1920, and the resolution was filed with the Oregon Secretary of State on that day, January 14, 1920 is the actual date of Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. Special thanks to Layne Sawyer, Reference Manager at the Oregon State Archives, for her expertise and assistance with this question.

Western Oregon University students in Professor Kimberly Jensen’s History 410: Introduction to Public History class in Winter 2019 analyzed newspaper articles and editorial cartoons from the week of Oregon’s special session in the legislature. Learn more about Oregon’s ratification story in their special exhibit below, as a joint project with the Oregon Women’s History Consortium. Our thanks to the Western Oregon University History Department, WOU History chair Elizabeth Swedo, and WOU President Rex Fuller for their support and to Maggie Triplett at Petals and Vines in Monmouth for help in recreating the carnation bouquet.

Exhibit Sections

Scroll Through the Exhibit, or Click on Specific Sections Here

Antonia Scholerman, “Thompson’s Authority Undermined”

Spencer Kennedy, “Fake News is Not a New Invention” and “Elbert Bede Refuses to Let ‘Progressive’ Picture Prevail: Mentions Falsehood in His Recap of Special Session”

Abigail Freimark, “Defending Her Honor”

Matthew Ciraulo, “One Woman’s Fight for Equality and Strength for all Women”

Matthew Capellen, “‘Smoothed Out the Waters'”

Colin Gilbert, “House Joint Resolution No. 1”

Thompson’s Authority Undermined

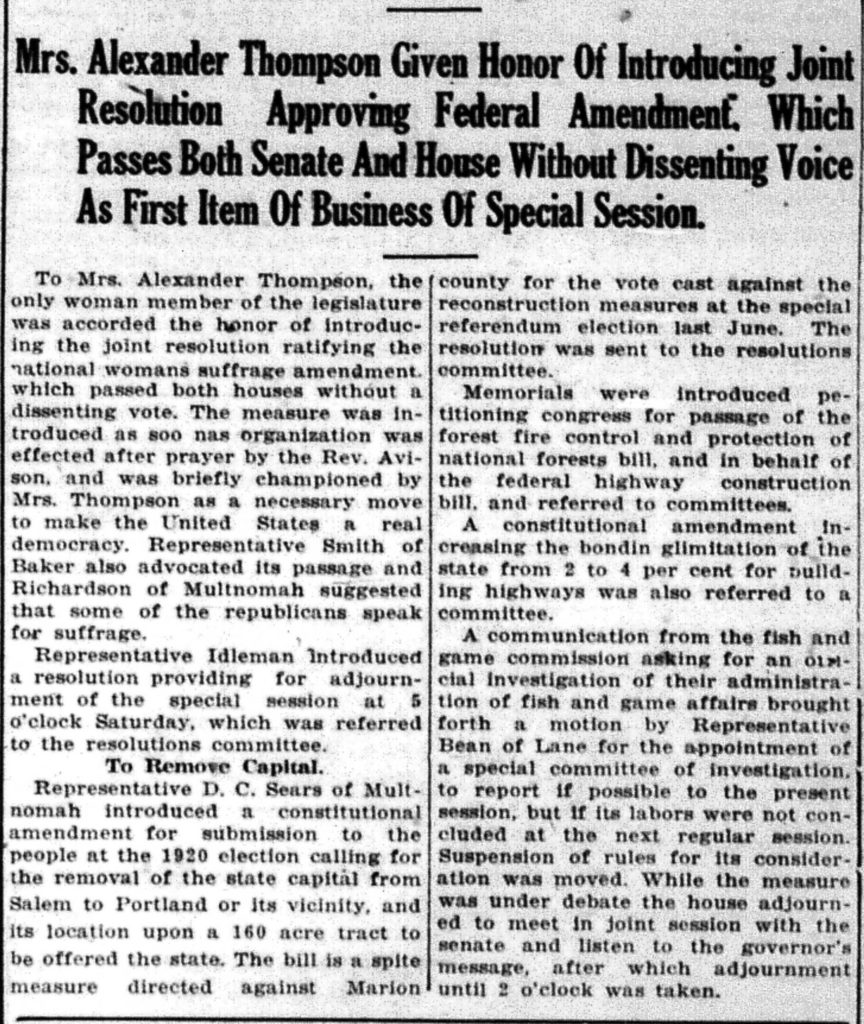

On the evening of Monday, January 12, 1920 the editors of the Salem Capital Journal gave a summary of the legislature’s special session. (“Mrs. Alexander Thompson Given Honor,” Salem Capital Journal, January 12, 1920, 1.) Some of the topics of discussion included changing Oregon’s capital to Portland (which the article mentions is a “spite measure”), building highways, the Fish and Game Commission, the protection of national forests, and the Oregon ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. There was no opposition to the ratification during this special session, and as the article notes, Representative Sylvia Thompson had the honor of introducing the Joint Resolution in the House of Representatives.

While Thompson was a member of Oregon’s House of Representatives, she was not commonly referred to as such, especially in the press. Here she was “Mrs. Alexander Thompson.” The lack of title, whether this was acknowledged or not, undermined her authority as a state representative. Because the press referred to her by her husband’s name, she did not seem to hold the same respect as a male counterpart would. She was not called a representative, and her first name does not appear in the text. Although the ratification was “a necessary move to make the United States a real democracy,” not everyone in the Oregon state legislature received the same treatment. —Antonia Scholerman [return to sections list]

Fake News is Not a New Invention

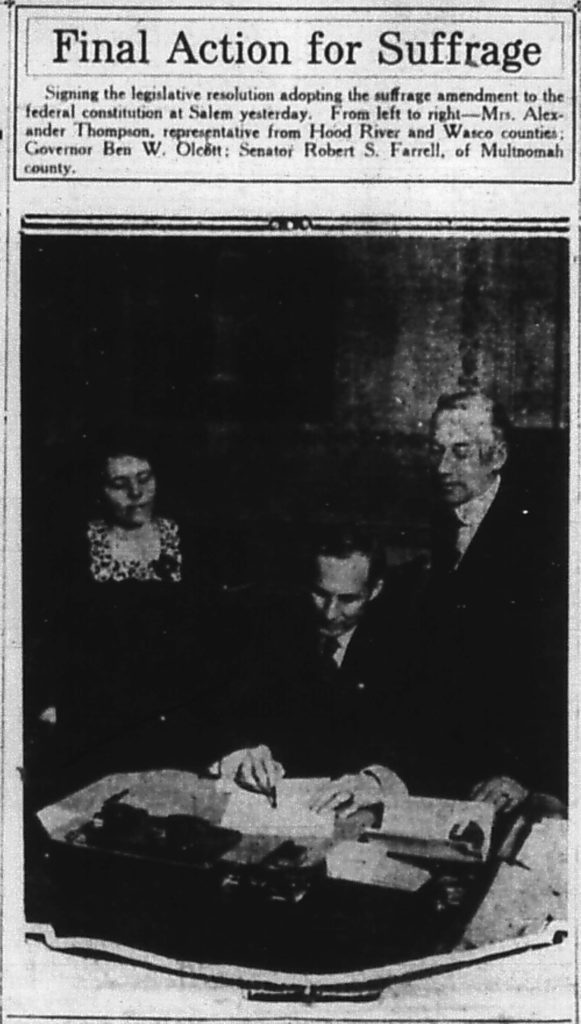

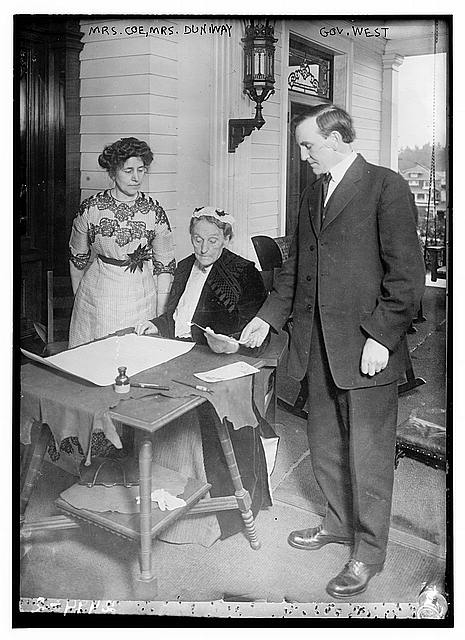

On Tuesday, January 13, in the midst of the suffrage voting excitement, the Portland Telegram published “Final Action for Suffrage.” This article consisted of a photograph and a caption and the photograph included was sure to make any other photographer jealous. (“Final Action for Suffrage,” Portland Evening Telegram, January 13, 1920, 1.) It depicted the signing of a Joint Resolution ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment by Governor Ben Olcott surrounded by Representative Sylvia Thompson and Senator Robert Farrell, the two sponsors of the joint resolution for ratification.

The picture seemed to echo the Viola Coe, Abigail Scott Duniway, and Governor Oswald West photograph of the Oregon woman suffrage proclamation eight years earlier. Unfortunately, it soon came to light that the “Final Action Suffrage” photo was a fake. It was staged, as several other Oregon papers such as the Oregon Journal and the Eugene Morning Register vehemently pointed out. Despite being a simpler era, fake news was still prevalent. However, with a free and independent media, they were able to call out this misinformation. —Spencer Kennedy [return to sections list]

An Over-Eager Portland Evening Telegram Photographer Staged a False Nineteenth Amendment Ratification Event. The Rival Oregon Journal Wasn’t Having It and Called Out “Fabrication of News!”

After the Portland Evening Telegram published “Final Action for Suffrage” on its front page on Tuesday, January 13, 1920, the editors of the rival Oregon Journal were gleeful. An “enterprising picture man” from the Telegram had posed Representative Thompson, Senator Farrell, and Governor West for what appeared to be the signing of a joint resolution before the ratification question had been resolved. It was “interesting but not true,” they wrote. “In the fabrication of news, The Telegram is a dandy. And in graphic depiction of said fabrication, The Telegram photographer is an able aide.” (“Timbergram is Picturesque and Eloquent Over Suffrage Bill,” Oregon Journal, January 13, 1920, 1.)

The editors of the Oregon Journal seemed especially pleased to call out their rival, the Portland Evening Telegram. They “renamed” their news competitor the “Timbergram,” with reference to the Telegram’s support for the timber industry, which the Oregon Journal editors opposed. The staged signing scene, they said, was “a fascinating group photograph” prepared for the Telegram’s front page, with “some supplementary fiction” about the signing.

By contrast, the Oregon Journal editors said their paper was reporting “the facts.” Because of the “squabble” in the legislature about whose name would be listed as the sponsor of the resolution, and about whether the House or Senate Resolution would be the one selected, the final joint resolution was not even ready for a vote Tuesday morning. But the outcome was not in doubt. “Immediate action on one measure or another is assured,” the Oregon Journal noted. But the Journal didn’t have all the facts. The editors reported that Governor Olcott would need to sign the resolution. But as you’ll see below that was not the way the process worked. –Kimberly Jensen [return to sections list]

Elbert Bede Refuses to Let “Progressive” Picture Prevail: Mentions Falsehood in His Recap of Special Session

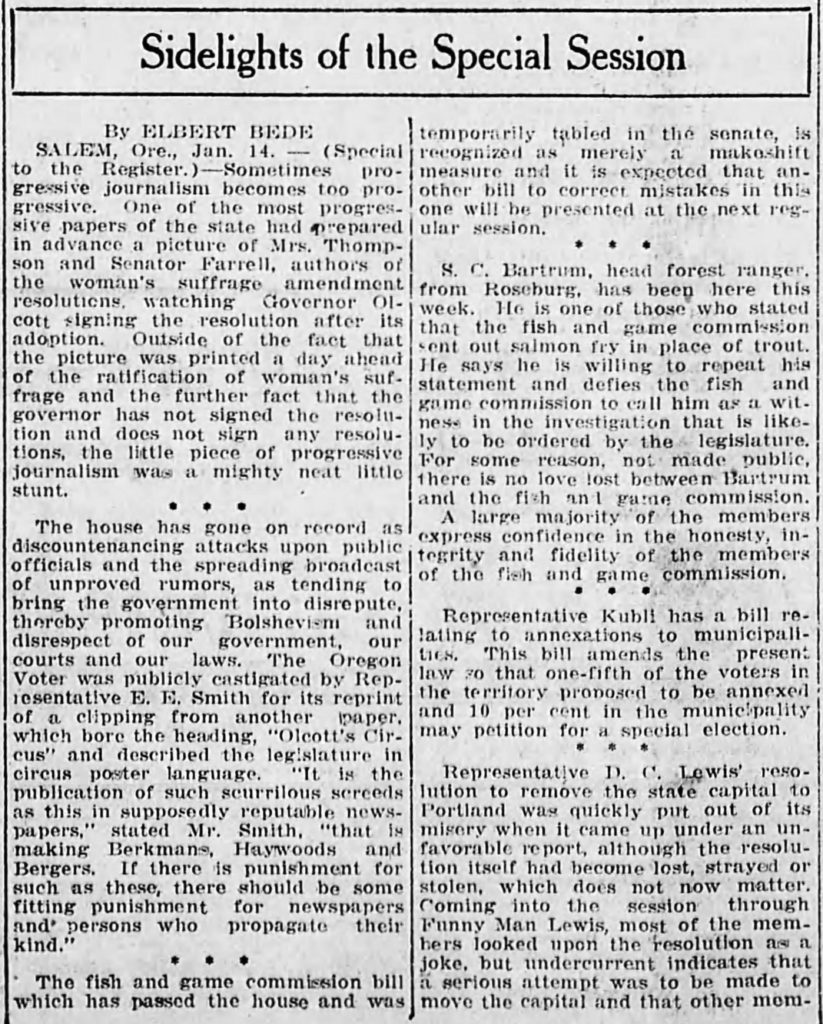

In an attempt to summarize the events of the Oregon State Legislative Special Session, Elbert Bede wrote “Sidelights of the Special Session” for the Eugene Morning Register, published on Friday January 16, 1920. He recapped several subjects including the house condemning rumors being spread about public officials, the controversial fish and game bill, and the resolution to move the capital to Portland. However, top billing went to something Bede referred to as, “a mighty neat little stunt” (Elbert Bede, “Sidelights of the Special Session,” Eugene Morning Register, January 16, 1920, 4.)

Bede told of the newspaper photographer who had prepared an advanced picture of “Mrs. Thompson and Senator Farrell . . . watching Governor Olcott signing the resolution (woman suffrage amendment) after its adoption.” While not referring to the paper by name, Bede described the picture found in the Portland Telegram’s “Final Action for Suffrage” published on its front page on Tuesday, January 13. Bede called it out as being a fabrication of news stating, “the picture was printed a day ahead of the ratification… and the further fact that the governor has not… and does not sign any resolutions.” He then criticized the Portland Telegram, mentioning that “sometimes progressive journalism becomes too progressive” referring to the fabrication and embellishment of this lie. He called into question the Telegram’s objectivity and trustworthiness. Having called out their “stunt,” Bede moved on to topics covered at the special session, leaving the Portland Telegram to mend its wounds from his written licking. —Spencer Kennedy [return to sections list]

Intense Rivalry of Thompson and Farrell “Broke Out into Open Flame” Over Authorship of the Amendment

The road to ratification was not an easy one. Especially for the ones who introduced the resolution in the first place. Representative Sylvia Thompson and Senator Robert Farrell were the two people who were responsible for bringing the equal suffrage ratification resolution into existence for Oregon. The authorship of the resolution itself was the main topic for discussion in this Oregon Journal article. (“Suffrage Honors at Stake: Mere Man Hurls Challenge, Woman Retorts to Kidders,” Oregon Journal, January 12, 1920, 1.) It started when Representative Benjamin Sheldon recommended that Representative Thompson’s name be added to the Senate Resolution sponsored by Senator Farrell. She was upset to learn this information and that she was being denied her part in the decision for her authorship of the House Resolution. Farrell and Thompson had a heated argument about their competing claims for authorship during a resolutions committee meeting. Both Thompson and Farrell fought for the honor of the claim toward recognition. The members of the committee teased that they would stand behind Thompson’s decision to switch to the Republican party, to which Thompson exclaimed that “she was done ‘with Os. West, Dr. Morrow and all that bunch.’” Despite the back and forth debate, the committee decided to table the resolution, which ended with Senator Farrell leaving the meeting very upset. The article ended with a cliffhanger: it would now be up to the members of the senate to decide if they would accept Thompson’s House Resolution on who would to leave their mark on Oregon history. — Kalea Borling [return to sections list]

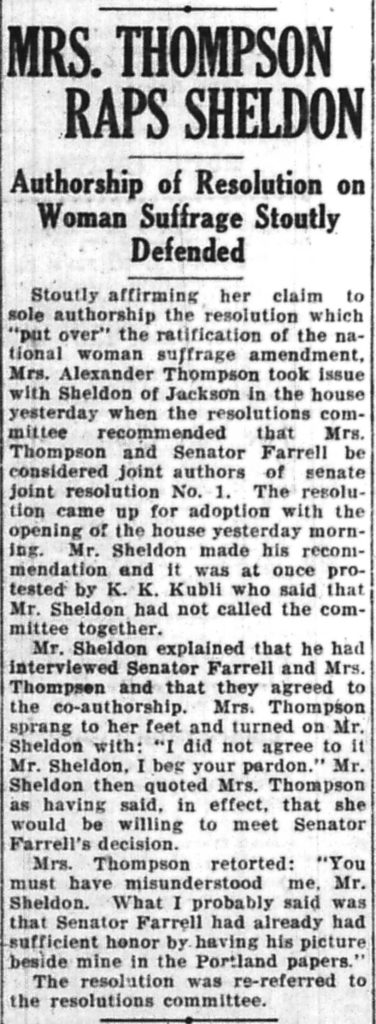

On January 14, 1920, the Salem Oregon Statesman published an article titled “Representative Thompson Raps Sheldon” on the sixth page of its paper. The article highlighted a discussion on January 13, during the second day of the special session, in which Representative Sylvia Thompson fervently defended her stance as sole author of the resolution that ratified the Nineteenth Amendment in Oregon. Representative Benjamin Sheldon suggested that Representative Thompson and Senator Robert Farrell be joint authors, but with the Senate Resolution that Farrell had authored, not the House Resolution Thompson had introduced. Representative K. K. Kubli protested because the committee on resolutions had not been asked to make this decision. Representative Sheldon claimed that Senator Farrell and Representative Thompson had agreed to co-sponsor the Senate resolution. (“Mrs. Thompson Raps Sheldon,” Oregon Statesman, January 14, 1920, 6.)

This moment was substantial. Representative Thompson, normally referred to only as “Mrs. Alexander Thompson,” was able to defend her stance as the first author of Oregon’s legislative resolution to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment and her position as a representative. Oregon women had achieved the vote just eight years earlier. Representative Thompson took full advantage of the opportunities now available to women in the state, and would not let this one be squandered over the choice of using the Senate Resolution introduced by Senator Farrell and being a co-author only. Her ability to stand her ground caused the resolution to be “re-referred to the resolutions committee,” and eventually ended with House Joint Resolution No. 1, introduced and authored solely by Representative Sylvia Thompson, standing as Oregon’s resolution to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. — Abigail Freimark [return to sections list]

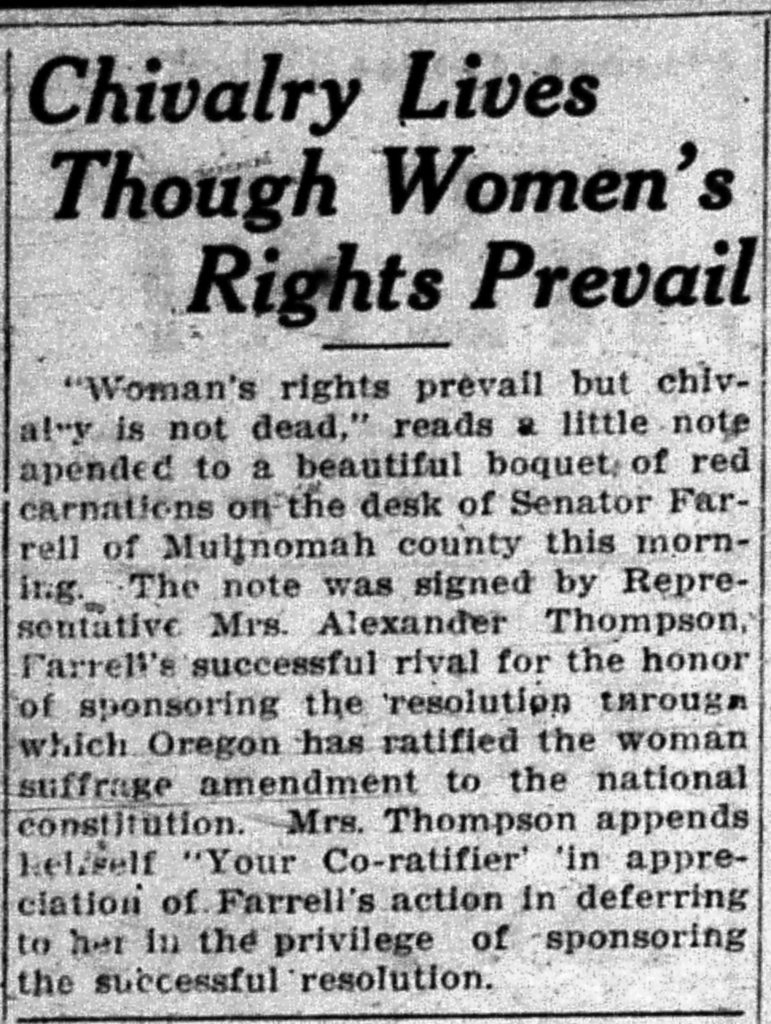

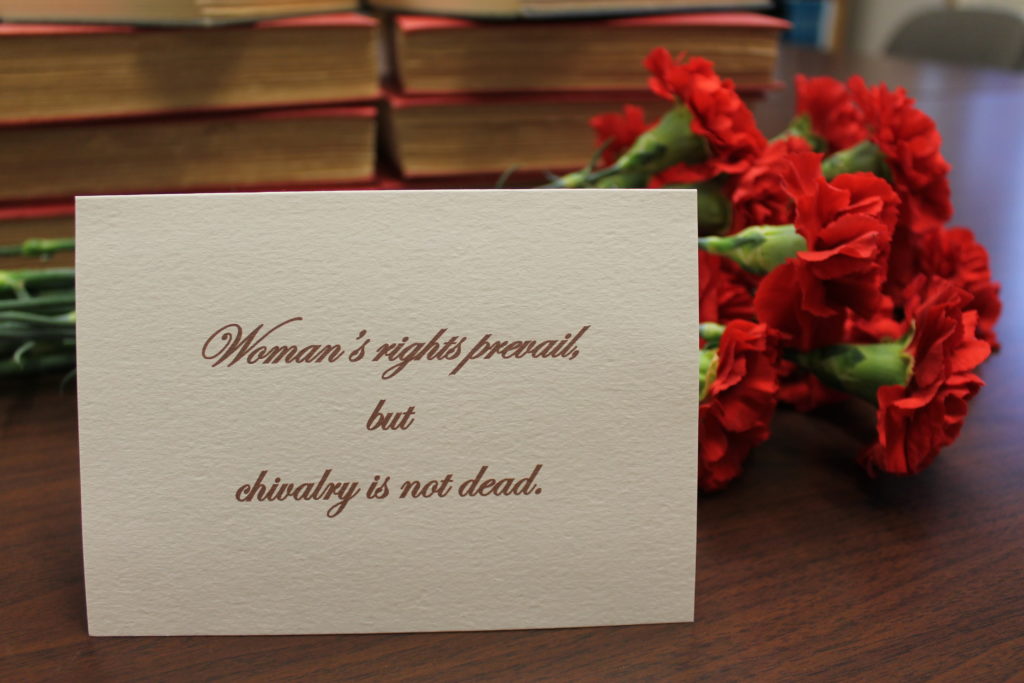

Chivalry Blooms as Representative Thompson Reverses Gender Roles in the Legislature

On Thursday, January 15, 1920, the Salem Capital Journal published an article describing an action taken by Representative Sylvia Thompson. Representative Thompson presented a bouquet of red carnations to Senator Robert Farrell. The bouquet was accompanied by a small card signed by Representative Thompson stating: “Woman’s rights prevail, but chivalry is not dead.” (“Chivalry Lives Though Women’s Rights Prevail,” Salem Capital Journal, January 15, 1920, 6.) Representative Thompson presented the bouquet after Senator Farrell deferred to her, but became her unofficial “co-ratifier” of the Oregon legislature’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. This came after some conflict about who would be the official sponsor.

The Capital Journal‘s editors showed support for the ratification in the story rather than making jest of the situation. They identified Thompson as “Representative” and chose to publish this brief story which showed Representative Thompson reversing gender roles in the legislature. The article presents Representative Thompson’s gift of the bouquet as an act of appreciation to Senator Farrell. But by publishing the text of the note, the editors emphasized Thompson’s tongue in cheek wit (“Woman’s rights prevail, but chivalry is not dead.”). The article made Farrell seem sympathetic in his graciousness while allowing Thompson’s determination to be put on  full display. —Hudson Kennedy [return to sections list]

full display. —Hudson Kennedy [return to sections list]

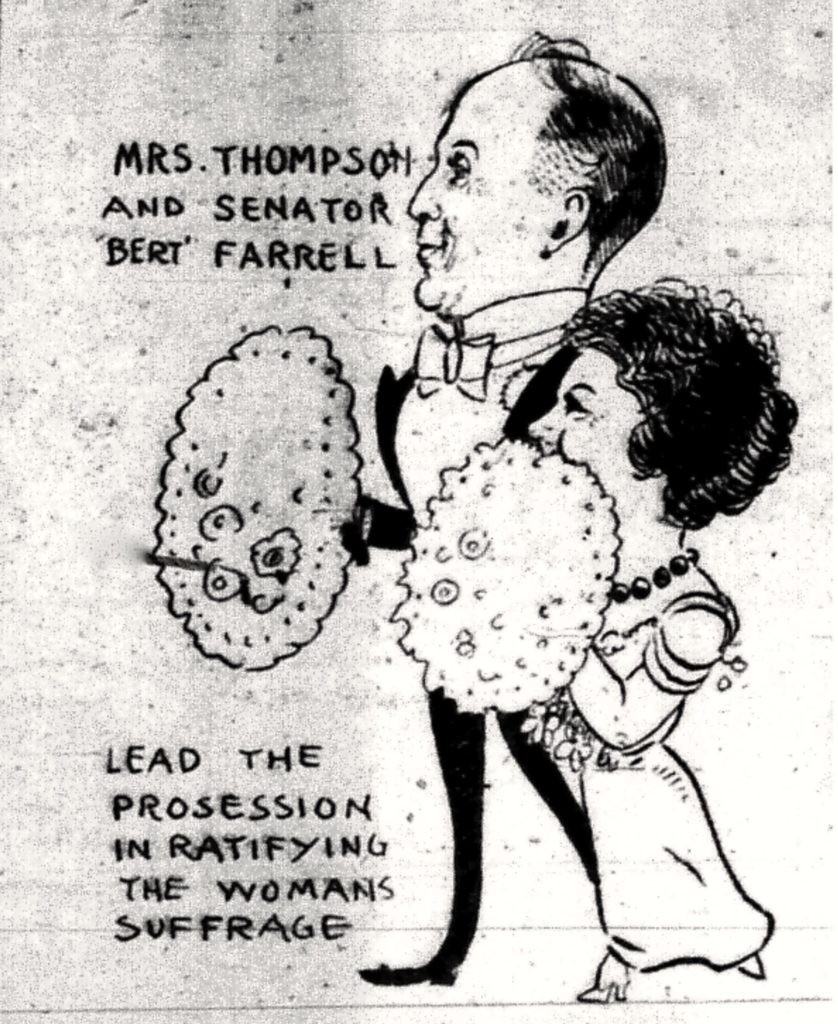

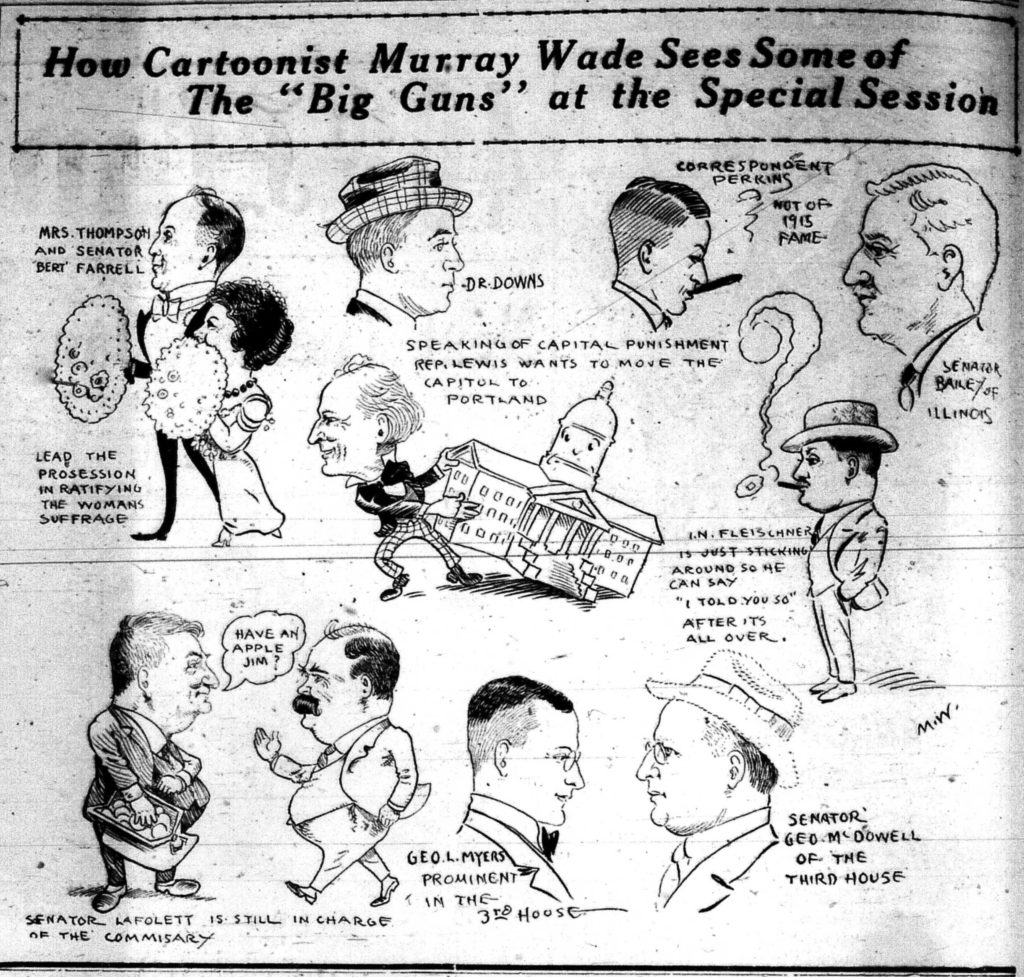

(Detail) Representative Sylvia Thompson and Senator Robert Farrell, with carnation bouquets, “lead the procession in ratifying the womans suffrage” at the 1920 Oregon special legislative session in the editorial cartoon by Murray Wade in the Salem Capital Journal.

One Woman’s Fight for Equality and Strength for all Women

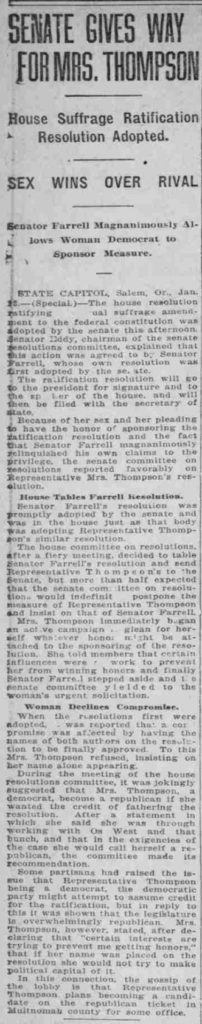

On January 14, 1920, the Oregonian informed readers that the House Joint Resolution for the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment would be passed to the senate president and speaker of the house for final signatures. Both Representative Sylvia Thompson and Senator Robert Farrell sponsored ratification bills. This was a woman’s issue and Thompson wanted to show the power of women and inspire other women to get involved politically. Her name on the resolution was much more than having the privilege of being the signer on a monumental and life changing resolution, but a message to all women that they can overcome and be successful. During her active campaign, Thompson brought to light that “certain influences were at work to prevent her from winning honors.” (“Senate Gives Way for Mrs. Thompson,” Oregonian, January 14, 1920, 6.) At one point some newspapers reported that Thompson and Farrell had agreed to co-sponsorship. Thompson declined and insisted that her name be the only signature appearing on the resolution. The roadblocks did not stop there. Coming into the process she identified with the Democratic Party, but during the process, the House Resolutions Committee members joked that Thompson should become a Republican if she wanted the credit for her resolution. Thompson responded she “was through working with Os West, and that bunch, and that in the exigencies of the case she would call herself a Republican.” Eventually Senator Farrell relinquished his claim.

This article has a lot to digest while it helps us determine a timeline for the date of Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. It gives the reader information about how many hoops Thompson had to jump through. There seemed to be a common occurrence of newspapers highlighting the drama around the process of ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment in Oregon. I wonder if the journalists’ views were reflected in the way that they were writing about the ratification, or if it was just for the purpose of entertaining the readers while informing them of statewide news? – Matthew Ciraulo [return to sections list]

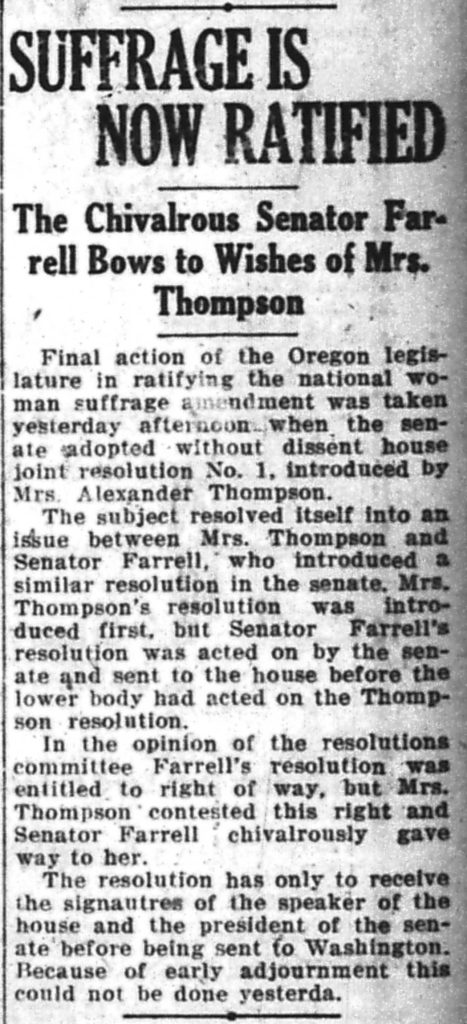

The Salem Oregon Statesman: “Suffrage is Now Ratified” as Senator Farrell “Bows to Wishes of Mrs. Thompson”

On Wednesday, January 14, 1920, the Salem Oregon Statesman published an article about the end of the conflict about the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Oregon legislature (“Suffrage is Now Ratified,” Oregon Statesman, January 14, 1920, 1.) The article demonstrated the relationship between Representative Sylvia Thompson, who was a representative in the Oregon House, and Senator Robert Farrell in the Oregon Senate. Both wanted the Nineteenth Amendment to be ratified. Tensions rose when Thompson introduced her resolution to the House but the Senate acted on Farrell’s Senate resolution first, before Thompson’s resolution made its way there. This gave Farrell the credit that Thompson deserved. The resolutions committee of the legislature felt that “Farrell’s resolution was entitled to right of way” but Senator Farrell recognized this and he respectfully gave Thompson the credit she deserved. Thompson’s House Resolution No. 1 became Oregon’s resolution of ratification on January 14, 1920. — Janessa Smith [return to sections list]

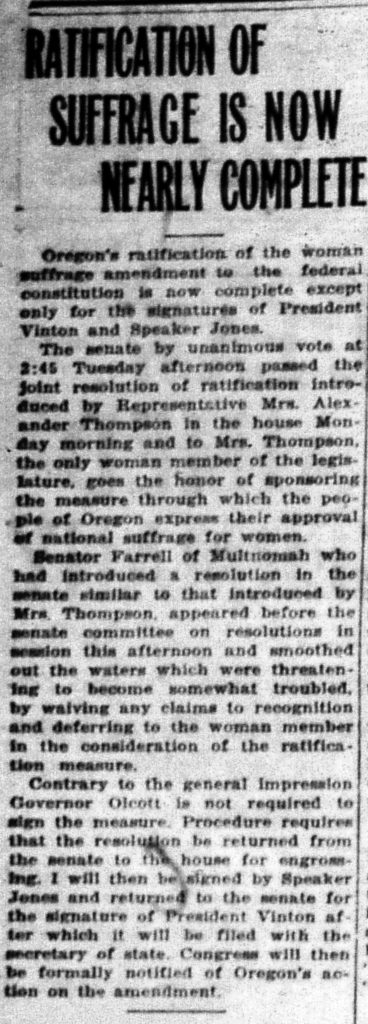

On Wednesday January 14, 1920 the Salem Capital Journal published a column announcing the final steps taken for Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. (“Ratification of Suffrage is Now Nearly Complete,” Salem Capital Journal, January 14, 1920, 2.) The editors noted that Senator Robert Farrell “smoothed out the waters” to end the conflict about sponsorship of the resolution by “waiving any claims to recognition.” This meant that Representative Sylvia Thompson, as the “only woman member of the legislature,” had the “honor of sponsoring the measure through which the people of Oregon express their approval of national suffrage for women.” To clear up confusion caused by other press reports that said Governor Ben Olcott would need to sign the resolution, the editors outlined the next steps for Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to be completed. After the signatures of Speaker of the House B. F. Jones and Senate President W.T. Vinton were collected, the resolution would be filed with the Office of the Secretary of State. —Matthew Capellen [return to sections list]

The Oregonian Publishes the Political Story of the Year: Oregon Becomes the Twenty-Fifth State to Ratify the Nineteenth Amendment

On January 15, 1920, the Oregonian published the story of the official state ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. (“Suffrage is Ratified,” Oregonian, January 15, 1920, 1.) Two key signatures were required in order for this new amendment to pull through and reach fruition. One was from the President of the Oregon Senate and the other from the Speaker of the House.

The press had made a number of errors during the ratification process. One of the mistakes made during the publication was that Governor Ben W. Olcott had a hand in the matter of signing the resolution when in fact he didn’t. The Joint Resolution only needed signatures from the House Speaker and Senate President.

Oregon became the 25th state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. Citizens nationwide finally possessed the right to vote regardless of sex identification. This marked one of the biggest changes in American history and still remains so to this day. — Evan Schwehr [return to sections list]

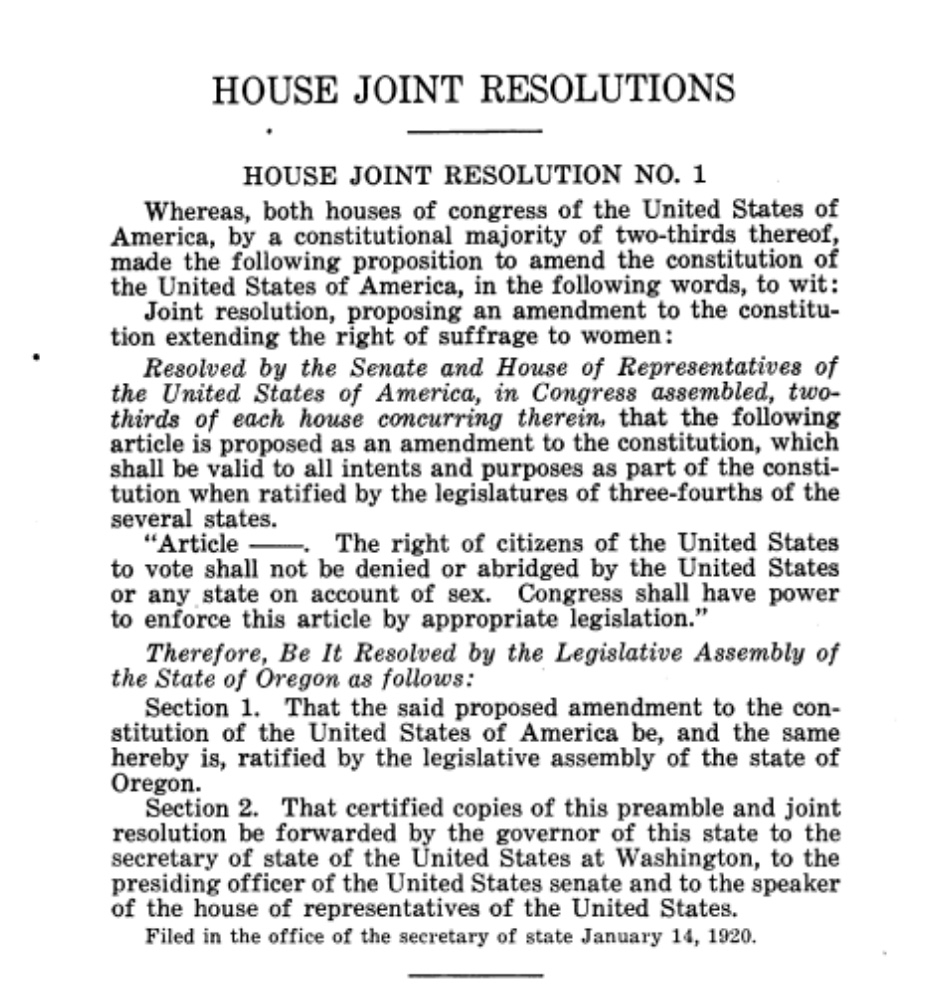

On Wednesday January 14, 1920, House Joint Resolution No. 1 became the official, signed document that the Oregon legislature passed to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment. At the beginning of the session, Governor Ben Olcott had asked the legislature to approve a resolution ratifying the amendment. Representative Sylvia Thompson’s House Joint Resolution prevailed, marking Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment.

The first section of the resolution described the proposed amendment that would “extend the right of suffrage to women.” House Joint Resolution No.1 also reviewed the process that the Amendment would need to be passed by a two-thirds majority of the House and Senate of the United States.

The Nineteenth Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any state on account of sex. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

House Joint Resolution No. 1 has two sections. Section 1 affirms that the Nineteenth Amendment was ratified by the Oregon State Legislature. Section 2 insures that the resolution will be forwarded to the officers in each chamber of the United States Congress. The Joint Resolution ends with a note that it was filed in the Secretary of State’s office on January 14, 1920, the official date of Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. —Colin Gilbert [return to sections list]

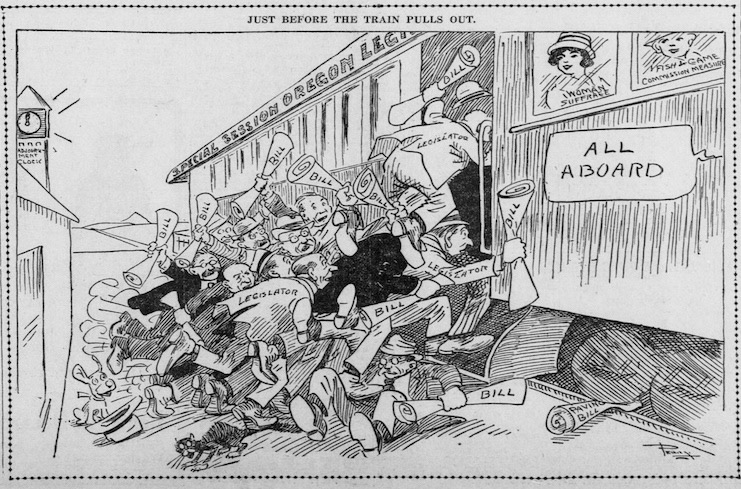

Legislative Dog Pile on the Platform, Spectators Watch From Their Comfortably Ratified Seats: A Look at How Events Transpired at the Oregon Legislative Special Session

This excellent editorial cartoon (H.H. Perry, “Just Before the Train Pulls Out,” Oregonian, January 17, 1920, 1.) depicted the frenzy of the special session of 1920 and is full of hints about the session. The departing train represented the woman suffrage resolution and Fish and Game Commission measure, both of which were passed in the session. However, numerous legislators tried to take advantage of the special session to push other bills onto the table for discussion. In the picture we see the legislators stumbling and crawling over each other in their haste to get their bill “on the train.” As we can see in the bottom right, some bills were not destined to make the cut and were discarded, or run over by the special session “train.” The overall picture this presents is one of chaos, a fantastic representation of how legislators were in a hectic rush to get their bill passed. In the end, the resolutions for the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment were the first items on the House and Senate dockets and passed within minutes of the session opening on January 12, 1920. Although it had passed in both houses, the resolution was not signed by the President of the Senate or the Speaker of the House until January 14. The Oregon ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was not official until it was signed by the necessary parties and filed with the Secretary of State on January 14, 1920. — Tyler Stauff [return to sections list]