January 1920 Around Oregon

Western Oregon University students explored additional information about the week of Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment from newspapers around the state. They share their comments on selected newspapers articles below.

Exhibit Sections

Scroll Through the Newspaper Articles, or Click on Specific Sections Here

Oregon City: Abigail Freimark, “Putting an End to Evil: Stamping Out the All-Night Dance”

Siletz, Lincoln County: Antonia Scholerman, “A Great Loss to Any Community”

St. Helens: Kalea Borling, “A Timeline of Woman Suffrage Ratification Across the United States”

Hood River: Matthew Capellen, “Discrimination Against Japanese Americans”

St. Johns: Hudson Kennedy, “St. Johns Review Supports Women’s Labor and Tries to Avoid Strikes”

Monmouth: Matthew Ciraulo, “Voices from Small Town Oregon”

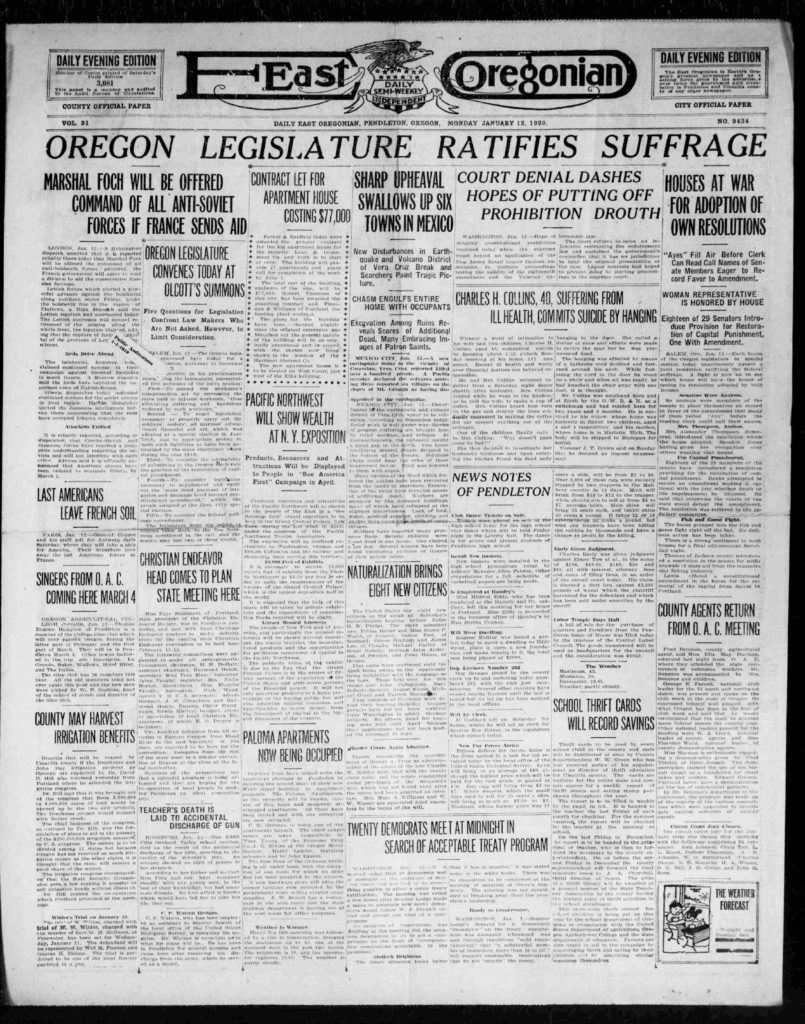

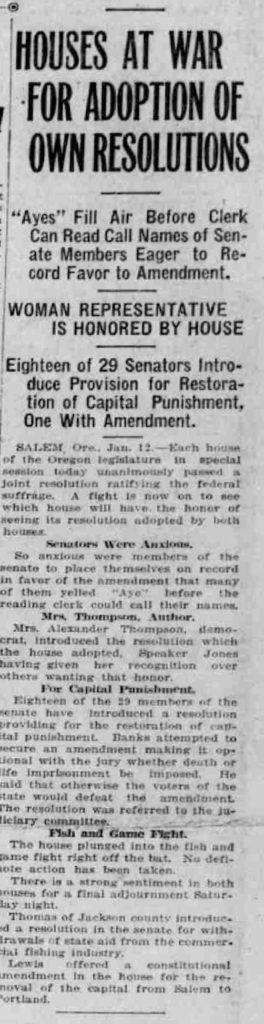

Pendleton East Oregonian Boldly Announces Ratification of Suffrage in Their Headline

On Monday January 12, 1920, Pendleton’s East Oregonian published its evening newspaper with the banner headline “Oregon Legislature Ratifies Suffrage.” Both the House and the Senate passed a Joint Resolution on the Nineteenth Amendment. Interestingly, the actual article that discusses the ratification in less than twenty lines in length. (“Houses at War for the Adoption of Own Resolutions,” East Oregonian, January 12, 1920, 1.) In an exciting header, the article begins with an emphatic retelling of the moment the vote happened in the senate chamber. The senators were so anxious about the vote that some of them called out “aye” before the clerk called their names.

The East Oregonian also mentions that a “Woman Representative” was honored by the house chamber. This woman was actually Representative Sylvia Thompson (though the article addresses her as Mrs. Alexander Thompson.) Sylvia Thompson was instrumental in ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment in Oregon. The newspaper also stated that House Speaker B.F. Jones gave her recognition “over others wanting that honor.” – Colin Gilbert [return to section list]

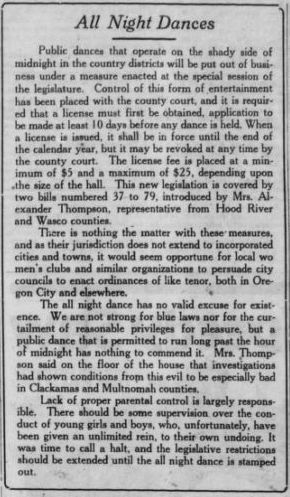

Oregon City Putting an End to Evil: Stamping Out the All-Night Dance

On Friday, January 23, a little over a week following Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Oregon City Enterprise published an article titled “All Night Dances” on the front page of their Friday paper. The article worked to validate and inform readers about “two bills numbered 37 to 79,” (“All Night Dances,” Oregon City Enterprise January 23,1920, 1.) introduced at the special legislative session by Representative Sylvia Thompson, who was not a fan of the all-night dance. The legislature passed both measures, which introduced new regulations, including required licenses for any all-night dances with the price of the license ranging from $5-$25. Although Thompson was a representative from Hood River and Wasco counties, after investigating she discovered that “conditions from this evil” (all-night dances) were rampant in both Clackamas and Multnomah counties. “Incorporated cities and towns” were not included under these measures, but they did serve as guidelines for city councils to enact restrictions on their own. One of the biggest issues talked about regarding the all-night dance was lack of supervision, and the creation of an environment that would give teenagers “an unlimited rein, to their own undoing.” Having attended evening dances in the twenty-first-century, they did not go all night. It is interesting that in the same session that ratified women’s right to vote, the rights of young people to dance freely all night were revoked in the name of protecting innocence. – Abigail Freimark [return to section list]

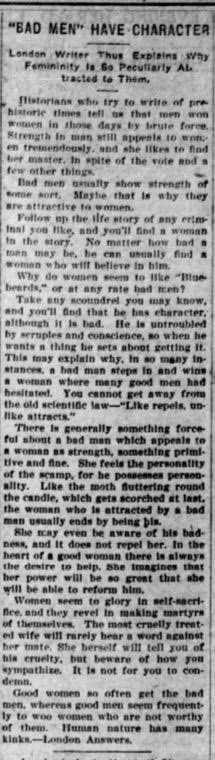

Klamath Falls “In Spite of The Vote and a Few Other Things”: Women Still Not Equal but Fear is Growing

On January 14, 1920, on the day of the vote to have Oregon ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, the editors of Evening Herald of Klamath Falls decided to publish the article “‘Bad Men’ Have Character.” This article, dripping with misogyny, toxic masculinity, and female degradation, told why every woman wants “to find her master in spite of the vote and other things.” (“‘Bad Men’ Have Character”, Klamath Falls Evening Herald, January 14, 1920, 3.) This opinion piece explained why “good women” fall for “bad men” referencing several broad fallacies, stereotypical generalizations, and offensive rhetoric.

This piece, which today might seem better suited to a tabloid than to a serious newspaper, took an in depth look into the “fact” that if one is to look into “the life story of any criminal . . . you’ll find a woman in the story.” The editorial, penned by someone known only as London Answers or London Writer, made unfounded claims such as Bad Men are “untroubled by scruples and conscience, so when he wants a thing he sets about getting it;” Bad Men are “forceful . . . which appeals to women;” and women may be aware of his badness and are trying to fix him because “women seem to glory in self-sacrifice, and . . . revel in making martyrs of themselves.” This article mentioned Blue Beard, a fictitious wealthy, violent man in the habit of murdering his wives and domestic abuse, reminding readers to “beware of how you sympathize. It is not for you to condemn.”

This article shows a glimpse into the mind of some men at the time. They saw the world falling apart at the seams and women were not there to mend it for them. Many men at this time were scared. They saw the patriarchy starting to crumble. This article shows them trying, desperately, to grasp at some kind of normality in their upside-down turning world. However, men of that time needn’t have worried too much. Despite advances in women’s rights, women are still not equal to men in the eyes of this country. Today women still make less money than men doing the same job, women are still underrepresented in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) community, and women’s right to choose what happens to their bodies is under attack. This is why we must continue to fight for women’s rights, safety, and equality, “In spite of the vote and a few other things.” —Spencer Kennedy [return to section list]

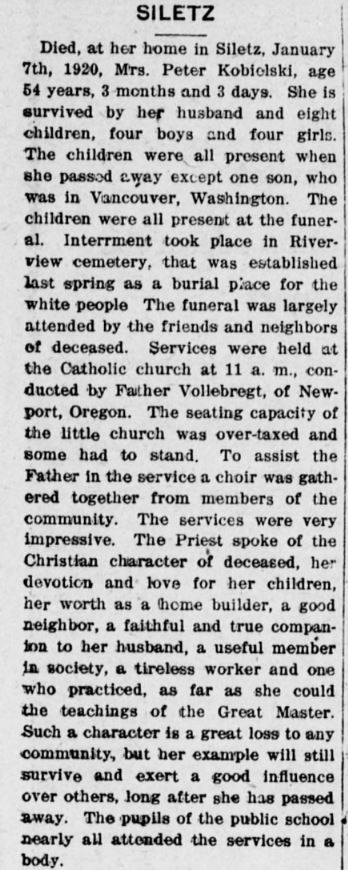

Siletz, Lincoln County A Great Loss to Any Community

The Lincoln County Leader was a weekly newspaper based out of Toledo, Oregon and the paper reported on events and news from all over Lincoln County. The front page was divided into sections where each town would have their portion to report news. Aside from the society pages, which explained who came to visit, who went out of town, and who had tea with whom, there was not much mentioned about women in the Lincoln County Leader of 1920. Occasionally there would be advertisements, such as one for Chamberlain’s Tablets, promising to permanently cure “periodic attacks of headache.” There was no mention of Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. There may be several reasons for this. Perhaps the authors of the newspaper did not care about woman suffrage, or maybe they did not think it was important enough to mention considering Oregon women had the right to vote since 1912.

On January 16, 1920, the town of Siletz included an obituary for a woman referred to in the paper as Mrs. Peter Kobielski, who passed away on January 7th at the age of fifty-four. (“Siletz,” Lincoln County Leader, January 16, 1920, 1.) She was buried in Riverview cemetery, a new burial site separated “for the white people.” She appears in 1920 census records as Paulina Kobielski. Although the author does not include her first name, opting to use her husband’s instead, the obituary includes details from the funeral service and Mrs. Kobielski’s activities while she was alive. This was unique, considering the near silence about individual women in the whole of the Lincoln County Leader. Mrs. Kobielski was actively involved in her church, community, and as a homebuilder, and the Priest spoke to her many good qualities. Conceivably, Paulina Kobielski can be considered representative of what it meant to be an exemplary woman of the time in Lincoln County. – Antonia Scholerman [return to section list]

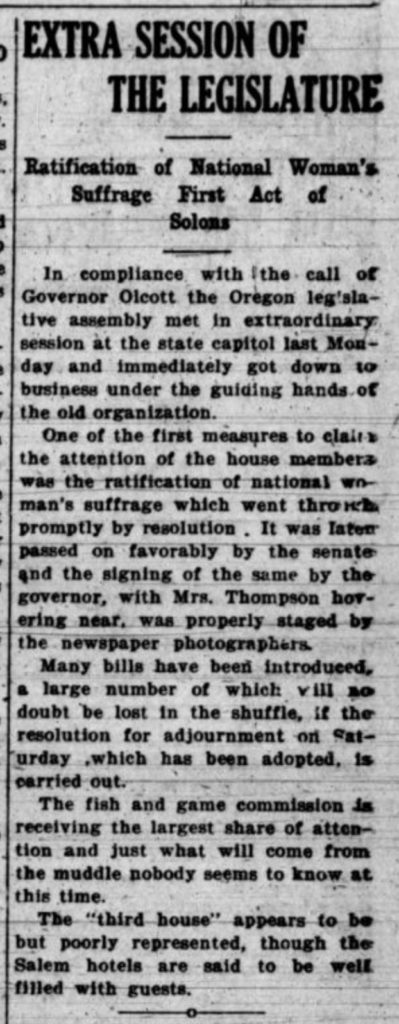

Newberg The Newberg Graphic Shines Light On A Rapid Special Session of the Oregon Legislature in January 1920. One of the Most Important Actions was the Ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment

On January 13, 1920, the Newberg Graphic published “Extra Session of the Legislature: Ratification of National Woman’s Suffrage First Act of Solons” (Newberg Graphic, January 13, 1920, 1.) Governor Olcott called the special legislative session, and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was one of the first actions of the legislature. The Newberg Graphic referenced the “Final Action for Suffrage” photograph in the Portland Telegram without knowing that the picture had been staged.

Excitement for this new amendment and the special session began to arise quickly throughout the State of Oregon. Many of the hotels in City of Salem had been “well filled with guests.” But there had not been many lobbyists present at the time. Despite the massive support from the likes of Salem and other cities across Oregon, there hadn’t been many lobbyists (members of the Third House).

Other bills were “lost in the shuffle.” But regardless, the most impactful resolution out of all of them at the time marked one of the biggest stages of civil rights and freedom in the United States. — Evan Schwehr [return to section list]

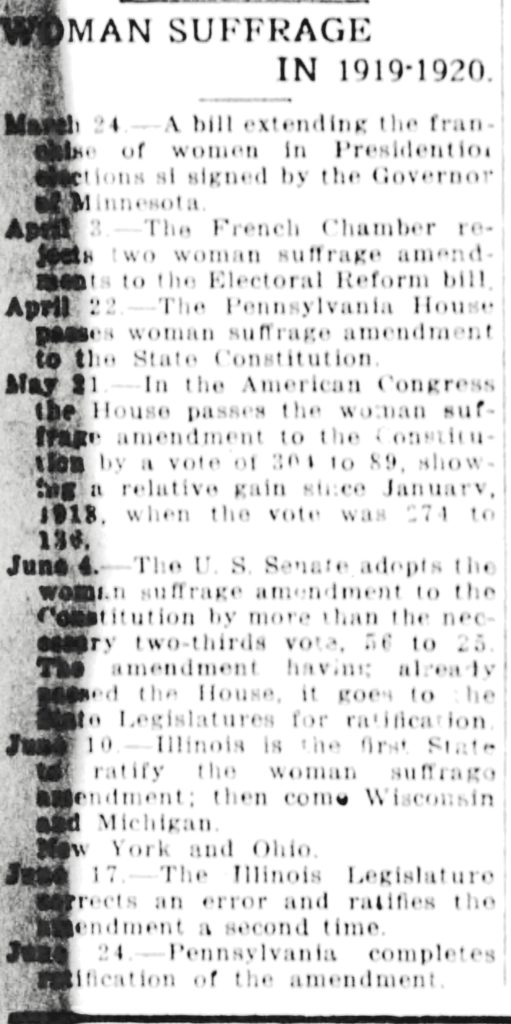

St. Helens A Timeline of Woman Suffrage Ratification Across the United States

In the history of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment for woman suffrage, it is helpful to organize the many events that took place that led to the eventual goal of ratification for Oregon and many other states. It often becomes confusing as the amendment was first introduced into the House and Senate and then was later ratified by 36 of the American states. An article published in the January 23, 1920 St. Helen’s Mist newspaper in St. Helens, Oregon, printed a timeline that sorted out the events of 1919 – January 1920 that related to the victory for women’s rights for Oregon and the states that ratified the Nineteenth Amendment before it. (“Woman Suffrage Timeline,” St. Helens Mist, January 23, 1920, 7.) The timeline started in March 1919 with the signing of the bill for the right of women to vote in presidential elections by the Governor of Minnesota. After the Nineteenth Amendment passed the U.S. House and Senate with a majority vote, Illinois was the first state to ratify the woman suffrage amendment. Wisconsin, Michigan, New York, Ohio, and twenty-two other states, including Oregon, ratified as well. By having the events laid out in this fashion, it is easy to see the dates and events that led each state to decide either for or against woman suffrage. This timeline is interesting to analyze as there was a dispute in what date was the true date of the ratification for Oregon. This timeline cites January 12, 1920 as the date that it was ratified, but there is conflicting information to consider when other sources say that it may have been January 14, 1920. It also contains key knowledge such as the fact that Alabama and Georgia rejected the amendment in July 1919. Of course, once ratified, the amendment would apply to all the states. But with a timeline, we are able to take these things into consideration when studying the dates and information that was taken on the road to ratification in all states.—Kalea Borling [return to section list]

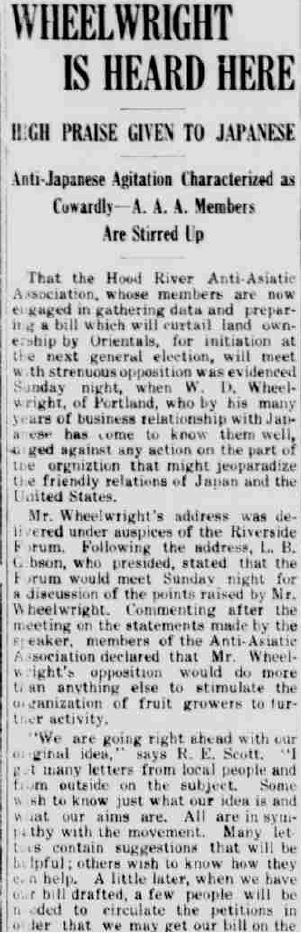

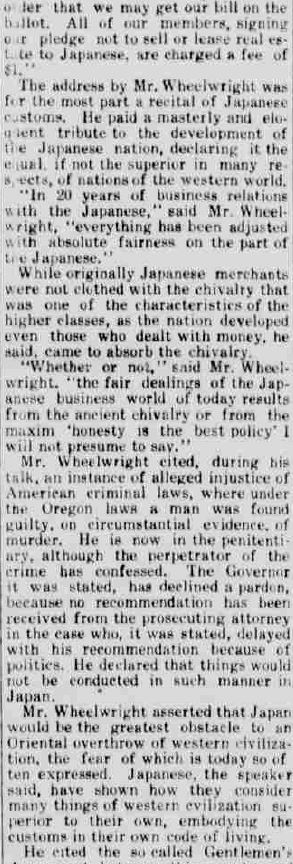

Hood River Discrimination Against Japanese Americans

The editors of the Hood River Glacier published “Wheelwright is Heard Here” (Hood River Glacier, January 8, 1920, 1.) This article starts off by saying current members of the Anti-Asiatic Association (AAA) were preparing to introduce a bill to be voted on during the next general election. The bill would prohibit first generation Japanese immigrants from owning land. W. D. Wheelwright, a businessmen from Portland who had dealt with Japanese and Japanese American business leaders over several years, countered the AAA at the Riverside Forum.

The editors of the Hood River Glacier published “Wheelwright is Heard Here” (Hood River Glacier, January 8, 1920, 1.) This article starts off by saying current members of the Anti-Asiatic Association (AAA) were preparing to introduce a bill to be voted on during the next general election. The bill would prohibit first generation Japanese immigrants from owning land. W. D. Wheelwright, a businessmen from Portland who had dealt with Japanese and Japanese American business leaders over several years, countered the AAA at the Riverside Forum.

After the meeting, AAA members declared Wheelwright’s opposition to their bill would only invigorate their activity in support of their measure. R. E. Scott, a member of AAA, noted that many people were sending him letters in support of their action and wanting to know more about their plans.

Wheelwright’s address focused on Japanese customs and national development. He commented on how fair the Japanese were in their business practices, and how consistent they were in regards to business. Wheelwright stated he was not sure if the fairness he received from the Japanese was from this chivalry or from the old saying “honesty is the best policy.” He stated acts against the Japanese were acts of “cowardice and national selfishness.” He provided statistics comparing population and land owned by Whites and Japanese in the Northwestern states to convince listeners not to fear a Japanese “overthrow of western civilization.”

Wheelwright appealed against the AAA’s bill due to possible tensions being created between the United States and Japan, which would be detrimental to their business relations. Despite his preaching about Japanese business, Wheelwright stated his strongest appeals were not related to it. The strongest appeal, he stated, would be for both America and Japan to exploit China so all three nations could benefit from the interaction. Wheelwright then made a call to action. Americans should match the Japanese in every regard and would have nothing to fear from the Japanese.

Even though the Nineteenth Amendment was for woman suffrage, not all women would be able to vote without being discriminated against, and many could not go to a ballot box. During this time period, racism was a major factor in America. Federal immigration laws prevented first generation Japanese Americans from becoming citizens and voting. Japanese American women and women of color faced discriminatory laws and social norms that limited their rights. —Matthew Capellen [return to section list]

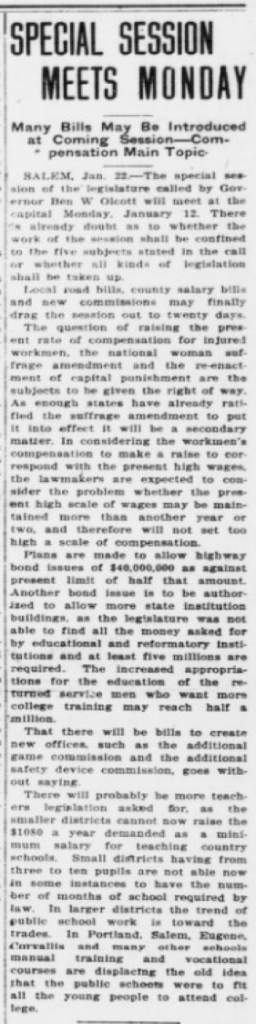

Springfield Insider’s View of What Is Expected at the Oregon Special Legislative Session

As we delve into the Springfield News on January 8, 1920, we can find a summary of some of the events taking place at the special session of the Oregon legislature. (“Special Session Meets Monday,” Springfield Review, January 8, 1920, 1.) The editors believed that Oregon’s ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment was a secondary matter based on the idea that it had already been ratified in enough states, when it actually had not. Oregon was the 25th state to ratify and 36 were needed. Because of this misconception, the editors believed the workers’ compensation bill to be the most important. They also emphasized the chaotic nature of the session by stating that it may “drag out to 20 days.” The Springfield News supported the Oregonian’s editorial cartoon “Just Before the Train Pulls Out“, from the Oregonian on January 17, 1920. They were correct about “all kinds of legislation shall be taken up” by the “dog pile” of legislators trying to get their bills on the session docket. This article also may shed more light onto why the paving bill was being run over by the train in the illustration. It would seem that the state was dealing with financial limits and not being able to spread the money around enough, as we see with the lack of funding to educational and reformatory institutions (approximately $5 million). With the supporters of the highway paving bill asking for double the limit, it is no wonder that it got shut down, or metaphorically run over. This article sheds light on some of the additional issues, attitudes, and functioning of the special session.–Tyler Stauff [return to section list]

St. Johns St. Johns Review Supports Women’s Labor and Tries to Avoid Strikes

The St. Johns Review published an article on Friday, January 16, 1920 on the Portland Woolen Mills and mill general manager and secretary E.L. Thompson. The article highlighted the benefits of working at the mill, specifically how the working conditions were superlative especially for female workers. The editors noted the plant supported a “give and take” proposition focusing on “perfect cooperation between employer and employee.” (“A Model Institution,” St. Johns Review, January 16, 1920, 4.) The editors’ word choice and examples of positives indicate an obvious support for Portland Woolen Mills and E.L. Thompson. The cooperation described is bookended by the editors’ indication that there has never been a strike in the history of the company and that the labor turnover was less than a tenth of the national average in 1918. A significant statement considering the burgeoning awareness concerning women’s labor rights, including the founding of the U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau that same year. The article painted a picture of contented and happy workers who have no reason to question the company’s authority.

The St. Johns Review published an article on Friday, January 16, 1920 on the Portland Woolen Mills and mill general manager and secretary E.L. Thompson. The article highlighted the benefits of working at the mill, specifically how the working conditions were superlative especially for female workers. The editors noted the plant supported a “give and take” proposition focusing on “perfect cooperation between employer and employee.” (“A Model Institution,” St. Johns Review, January 16, 1920, 4.) The editors’ word choice and examples of positives indicate an obvious support for Portland Woolen Mills and E.L. Thompson. The cooperation described is bookended by the editors’ indication that there has never been a strike in the history of the company and that the labor turnover was less than a tenth of the national average in 1918. A significant statement considering the burgeoning awareness concerning women’s labor rights, including the founding of the U.S. Department of Labor Women’s Bureau that same year. The article painted a picture of contented and happy workers who have no reason to question the company’s authority.

The editors’ support for the plant is continued when the article identifies the benefits that workers received, including an employee club house, where the hundreds of employees were served a “hearty lunch” for 25 cents every work day. These amenities become even more specific as the article stated that female workers had a “large, airy room all their own in a corner of the building upstairs.” At the time of the article’s writing the “nice resting places” and reasonable hours seem like new decisions, indicating a reaction to the increased awareness of women’s working rights. All of the examples chosen, and word choice utilized by editors, make the steps taken by the mill seem benevolent and supportive of women in the workplace. All of the choices by Mr. Thompson and the Portland Woolen Mills seemed to be appeasement of the workers. The fact that a strike had never occurred in the company’s history was praised by the editors. Cooperation and “give and take” were the methods supported by the St. Johns Review; which also indicates a negative view of strikes or radical change. This was especially apparent in the article when the description of the clubhouse for employees stated that it had “grown up with the family.” The editors praised the slow and familial growth of the mill. The new amenities provided for female workers by the Portland Woolen Mills show a new acceptance and support of women’s working rights, getting ahead of a social trend and avoiding a potential strike. —Hudson Kennedy [return to section list]

Monmouth Voices from Small Town Oregon

Monmouth Oregon is a rural town located halfway between Corvallis and Salem. It is home to one of Oregon’s oldest public universities, Western Oregon University. This rural community has been through its fair share of historical events, but one question kept pushing its way to the top: What did Monmouth, Oregon have to say about the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment?

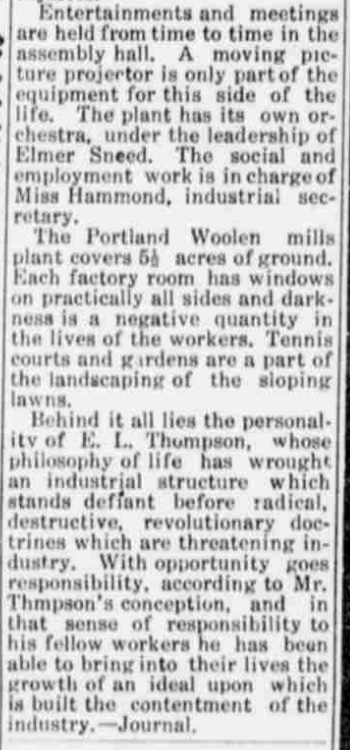

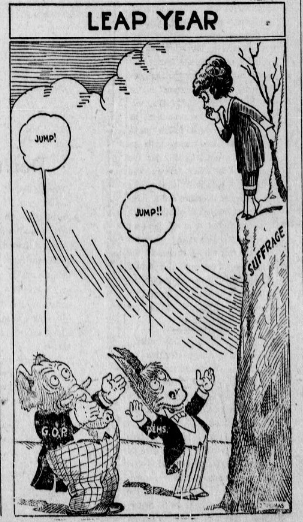

The Monmouth Herald of 1920 is what you might expect from a newspaper catering to a town primarily of farmers. It includes an abundance of advertisements and updates about the neighbors that call the Monmouth area home. One item of interest is an editorial cartoon titled “Leap Year,” which was also being used as a cartoon in other newspapers at this time. (“J. Thomas, “Leap Year,” Monmouth Herald, January 16, 1920, 1.) The history of Leap Year was an excuse to reverse gender roles allowing women power that wasn’t normally associated with them. The phenomenon occurs when February has twenty-nine days and was observed well into the 20th century within the United States. The title of the cartoon is playing off of this “societal norm” portraying the fact that this is the year that women have the power, and the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment is on their agenda. The cartoon was created J. Thomas and was a nationally-syndicated appearing in many newspapers. After the ratification it seems to reference women voters’ choice between voting as Republicans or Democrats and the parties, represented by the animals, hoping that they choose them. Even though it was created for a more general audience, the cartoon could symbolize Representative Sylvia Thompson, as she was the creator and signer of Oregon’s ratification resolution. The illustration could also represent her decision of staying a Democrat or becoming a Republican to receive credit for her resolution.

The Monmouth Herald contains little information about the events that were happening on a state or federal level. A section titled “Monmouth Meditations” compiled current events happening that week. A second item of interest is the small update informing the residents of Monmouth that Oregon joined the ranks of suffrage ratifying states. What is interesting is in the segment that states “when the average woman learns how to vote she will beat the average man who has been studying the art for a hundred years.” (“Monmouth Meditations,” Monmouth Herald January 16, 1920, 2.) There seems to be confusion on how this should be interpreted. My friends, classmates, and professor are conflicted on whether the author was writing in a condescending tone suggesting that women will not be as good as men because they had been voting for hundreds of years, or congratulating women, believing they will surpass the men based on their determination and strength of ratifying the Nineteenth Amendment. Due to a century-long gap, it is unclear how the author of the statement meant for the audience to interpret it. We must entirely base it on our interpretation; however, I would never have imagined such a potentially controversial statement from a small town newspaper.—Matthew Ciraulo [return to section list]

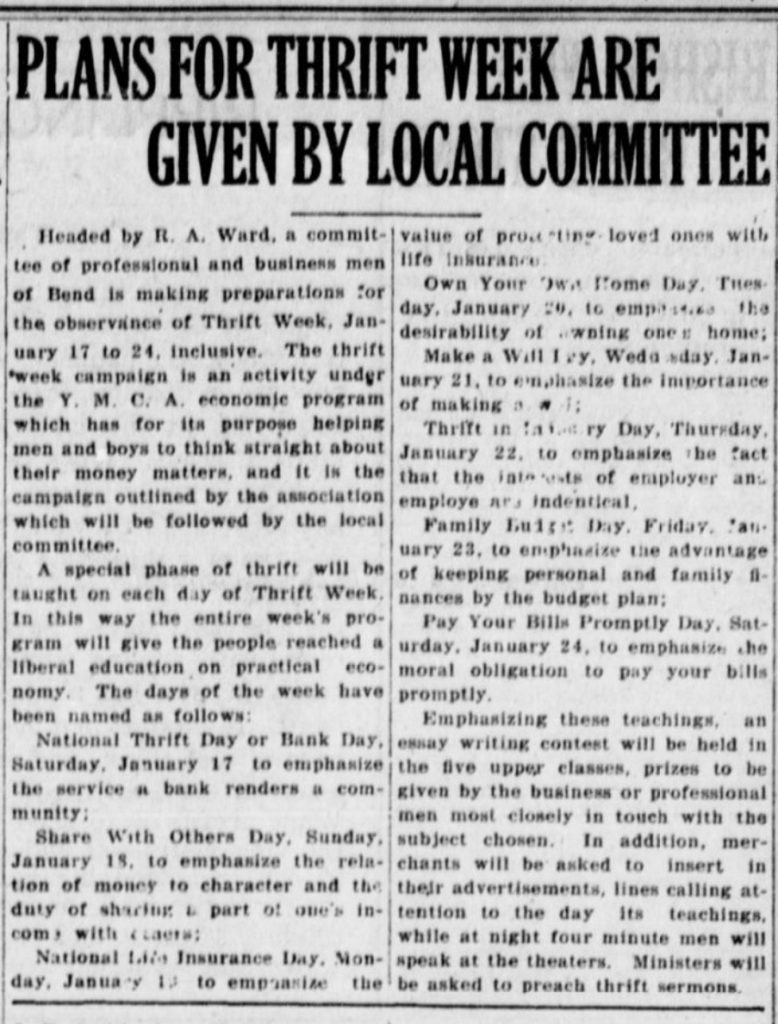

Bend After the Nineteenth Amendment Ratified, the Bend Bulletin Excludes Women During “Thrift Week”

Six days after the start of Oregon’s special legislative session, the men of Bend, Oregon created a “Thrift Week,” which would help young men and businessmen learn the important skills of thrifting. (“Plans for Thrift Week Are Given by Local Committee,” Bend Weekly Bulletin, January 15, 1920, 3.) R. A. Ward headed the committee, which decided to spend the week after the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment specifically helping men. The idea behind the campaign was, “an activity under the Y.M.C.A. economic program which has for its purpose helping men and boys to think straight about their money matters, and it is the campaign outlined by the association which will be followed by the local committee.” They created a thrifty theme per day during that week to “educate on practical economy.”

Saturday, January 17, was “National Thrift Day or Bank Day” which was to help men understand how and what a bank can offer a community. Sunday, January 18 was “Share with Others Day” which was meant to help the men in the community understand the “relationship of money to character.” They wanted to ensure everyone understood their part in their local economy. Monday, January 19 was “National Insurance Day” to emphasize the “value of protecting loved ones with life insurance.” Tuesday, January 20 was “Own Your Own Home Day” to emphasize the value and ownership of owning property. Wednesday, January 21 was “Make a Will Day” to emphasize the importance of making a will for loved ones. Thursday, January 22 was “Thrift in Labor Day” which emphasized that interest should be equal among employers and employees. Friday, January 23, was “Family Budget Day,” which emphasized “the advantages of keeping personal and family finances by the budget plan.” The last day, Saturday, January 24 was “Pay Your Bills Promptly Day” to emphasize the importance on paying one’s bills on time. Throughout the week organizers held writing contests with prizes given to men “most closely in touch with the subject chosen.” Ministers were also asked to preach thrift sermons.

The week’s events taught the young boys and men valuable skills to be financially stable for their time and to care for others in any way possible. However, “Share with Others Day”, should have at the very least included women. The Nineteenth Amendment had been ratified only six days before the events took place. This suggests that women in Bend, Oregon were trusted with their votes, but not their family’s money. –Janessa Smith [return to section list]